Swift Concurrency—Part 1: Tasks, Executors, and Priority Escalation

Swift 6 introduced a new approach to concurrency in apps. In this article, we will explore the problems it aims to solve, explain how it works under the hood, compare the new model with the previous one, and take a closer look at the Actor model. In the upcoming parts, we will also break down executors, schedulers, structured concurrency, different types of executors, implement our own executor, and more.

Swift Concurrency Overview: Problems and Solutions

Concurrency has long been one of the most challenging aspects of software development. Writing code that runs tasks simultaneously can improve performance and responsiveness, but it often introduces complexity and subtle bugs as race conditions, deadlocks, and thread-safety issues.

Swift Concurrency, introduced in Swift 6, aims to simplify concurrent programming by providing a clear, safe, and efficient model for handling asynchronous tasks. It helps developers to avoid common pitfalls by enforcing strict rules around data access and execution order.

\

\ Some of the key problems Swift Concurrency addresses include:

- Race Conditions: Preventing simultaneous access to shared mutable state that can cause unpredictable behaviour.

- Callback hell: Simplifying asynchronous code that used to rely heavily on nested callbacks or completion handlers, making code easier to read and maintain.

- Thread management complexity: Abstracting away low-level creation and synchronization, allowing developers to focus on the logic rather than thread handling.

- Coordinating concurrent tasks: Structured concurrency enables clear hierarchies of tasks with proper cancellation and error propagation.

By leveraging new language features like async/await, Actors, and structured concurrency, Swift 6 provides a more intuitive and robust way to write concurrent code, improving both developer productivity and app stability.

Multitasking

Modern operating systems and runtimes use multitasking to execute units of work concurrently. Swift Concurrency adopts cooperative multitasking, which differs fundamentally from the preemptive multitasking model used by OS-level threads. Understanding the difference is key to writing performant and safe asynchronous Swift code.

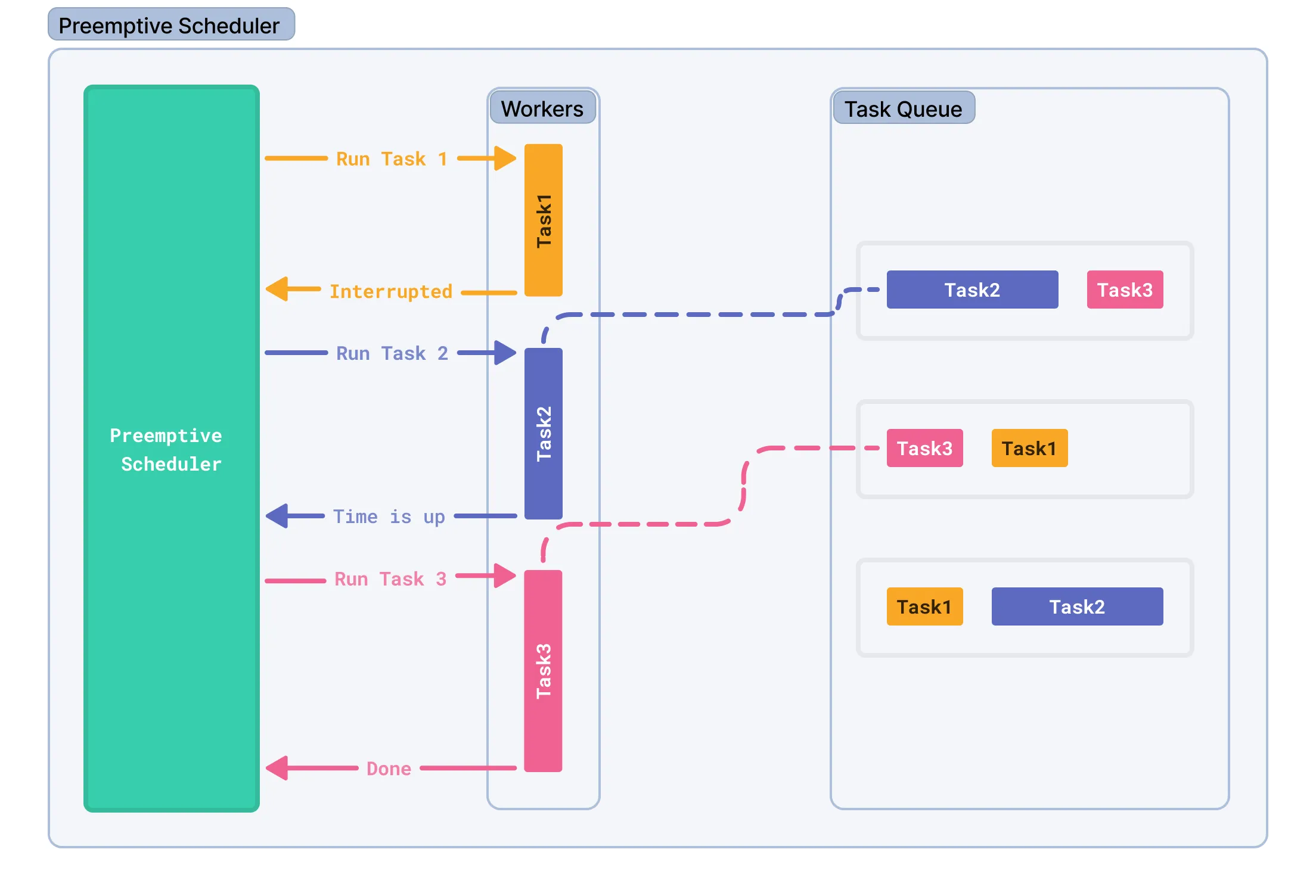

Preemptive Multitasking

Preemptive multitasking is the model used by operating systems to manage threads and processes. In this model, a system-level scheduler can forcibly interrupt any thread at virtually any moment to perform a context switch and allocate CPU time to another thread. This ensures fairness across the system and allows for responsive applications — especially when handling multiple user-driven or time-sensitive tasks.

Preemptive multitasking enables true parallelism across multiple CPU cores and prevents misbehaving or long-running threads from monopolizing system resources. However, this flexibility comes at a cost. Because threads can be interrupted at any point in their execution — even in the middle of a critical operation — developers must use synchronization primitives such as mutexes, semaphores, or atomic operations to protect shared mutable state. Failing to do so may result in data races, crashes, or subtle bugs that are often difficult to detect and reproduce.

This model offers greater control and raw concurrency, but it also places a significantly higher burden on developers. Ensuring thread safety in a preemptive environment is error-prone and may lead to non-deterministic behavior — behavior that varies from run to run — which is notoriously difficult to reason about or reliably test.

\

From a technical perspective, preemptive multitasking relies on the operating system to handle thread execution. The OS can interrupt a thread at almost any point — even in the middle of a function — and switch to another. To do this, the system must perform a context switch, which involves saving the entire execution state of the current thread (such as CPU registers, the instruction pointer, and stack pointer), and restoring the previously saved state of another thread. This process may also require flushing CPU caches, invalidating the Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB), and transitioning between user mode and kernel mode.

These operations introduce significant runtime overhead. Each context switch takes time and consumes system resources — especially when context switches are frequent or when many threads compete for limited CPU cores. Additionally, preemptive multitasking forces developers to write thread-safe code by default, increasing overall complexity and the risk of concurrency bugs.

While this model provides maximum flexibility and true parallelism, it’s often excessive for asynchronous workflows, where tasks typically spend most of their time waiting for I/O, user input, or network responses rather than actively using the CPU.

Cooperative Multitasking

In contrast, Swift’s concurrency runtime uses cooperative multitasking. In this model, a task runs until it voluntarily yields control — typically at an await point or via an explicit call to Task.yield(). Unlike traditional threads, cooperative tasks are never forcibly preempted. This results in predictable execution: context switches occur only at clearly defined suspension points.

Swift’s cooperative tasks are scheduled onto a lightweight, runtime-managed cooperative thread pool—separate from Grand Central Dispatch queues. Tasks running in this pool are expected to be “good citizens,” yielding control when appropriate, especially during long-running or CPU-intensive work. To support this, Swift provides Task.yield() as a manual suspension point, ensuring other tasks have a chance to execute.

However, cooperative multitasking comes with a caveat: if a task never suspends, it can monopolize the thread it’s running on, delaying or starving other tasks in the system. Therefore, it is the developer’s responsibility to ensure that long-running operations include suspension points.

In cooperative multitasking, the fundamental unit of execution is not a thread, but a chunk of work, often called a continuation. A continuation is a suspended segment of an asynchronous function. When an async function suspends at an await, the Swift runtime captures the current execution state into a heap-allocated continuation. This continuation represents a resumption point and is enqueued for future execution.

Instead of associating a thread with a long-running task, the Swift runtime treats a thread as a pipeline of continuations. Each thread executes one continuation after another. When a continuation finishes or suspends again, the thread picks up the next ready continuation from the queue.

As mentioned above, this model avoids traditional OS-level context switches. There is no need to save and restore CPU registers or thread stacks; the runtime simply invokes the next closure-like continuation. This makes task switching very fast and lightweight, though it involves increased heap allocations to store the suspended async state.

The key trade-off: you use a bit more memory but gain dramatically lower overhead for task management. Cooperative scheduling gives tight control over when suspensions happen, which improves predictability and makes concurrency easier to reason about.

Introducing to Task

In Swift Concurrency, a Task provides a unit of asynchronous work. Unlike simply calling an async function, a Task is a managed object that runs concurrently with other tasks in a cooperative thread pool.

Tasks can be created to run concurrently, and they can also be awaited or canceled. They provide fine-grained control over asynchronous behavior and are an integral part of structured concurrency in Swift.

Creating a Task

A task can be created using the Task initializer, which immediately launches the provided asynchronous operation:

Task(priority: .userInitiated) { await fetchData() }

When you create a Task using the standard initializer (i.e. not detached), it inherits the surrounding actor context, priority, and task-local values. This behavior is crucial for structured concurrency and safety in concurrent code.

Under the hood, in earlier versions of Swift Concurrency, the Swift runtime used an internal mechanism called @_inheritActorContext to track which actor a task was associated with. Although this property wasn’t part of the public API, it played a key role in ensuring that tasks created inside actor-isolated code would execute on the same actor, preserving data race safety.

With advancements in Swift, the runtime has started transitioning from @_inheritActorContext to a new mechanism known as sending, which is now more explicitly handled by the compiler and runtime.

\ When you launch a Task.detached, you must ensure that any values captured by the task are Sendable. The compiler now enforces this at compile-time using Sendable protocol and the @Sendable function type.

Failing to conform to Sendable may result in a compile-time error, particularly in strict concurrency mode.

Tasks also support priorities, similar to how Grand Central Dispatch queues handle them.

Task vs Task.detached

When working with Swift Concurrency, it’s important to understand the difference between Task and Task.detached, as they define how and where asynchronous work is executed.

Task

Task inherits the current actor context (such as MainActor or any custom actor) and priority. It’s commonly used when you want to spawn a new asynchronous operation that still respects the current structured concurrency tree or actor isolation. This is especially useful for UI updates or working inside specific concurrency domains.

Task { await updateUI() }

In the example above, if called from the main actor, the Task will also run on the main actor unless explicitly moved elsewhere.

Task.detached

Task.detached creates a completely independent task. It doesn’t inherit the current actor context or priority. This means it starts in a global concurrent context and requires manage safety, especially when accessing shared data.

Task.detached { await performBackgroundWork() }

Use Task.detached when you need to run background operations outside the current structured context, such as long-running computations or escaping an actor’s isolation.

Cooperative Thread Pool

Swift Concurrency operates using cooperative thread pool designed for efficient scheduling and minimal thread overhead. Unlike traditional thread-per-task executing model, Swift’s approach emphasizes structured concurrency and resource-aware scheduling.

A common oversimplification is to say that Swift Concurrency uses one thread per core, which aligns with its goal to reduce context switching and maximize CPU utilization. While not strictly false, this view omits important nuances about quality-of-service buckets, task priorities, and Darwin scheduler behavior.

Thread Count: Not So Simple

On a 16-core Mac, it’s possible to observe up to 64-threads managed by Swift Concurrency alone - without GCD involvement. This is because Swift’s cooperative thread pool maps not just per-core, but per core per QoS bucket.

Formally:

Max threads = (CPU cores) × (dedicated quality-of-service buckets)

Thus, on a 16-core system:

16 cores × 4 QoS buckets = 64 threads

Each QoS bucket is essentially a dedicated thread lane for a group of tasks sharing similar execution priority. These are managed internally by Darwin’s thread scheduling mechanism and are not the same as GCD queues.

QoS Buckets and Task Priority

Although TaskPriority exposes six constants, some of them are aliases:

usedInitiated→highutility→lowdefault→ already mapped tomedium

For the kernel’s perspective, this simplifies to 4 core priority levels, each mapped to a QoS bucket, which influences thread allocation in the cooperative thread pool.

When Does Overcommit Happen?

Under normal load, Swift Concurrency respects the cooperative pool limits. However, under contention (e.g. high-priority tasks waiting on low-priority ones), the system may overcommit threads to preserve responsiveness. This dynamic adjustment ensures that time-sensitive tasks aren’t blocked indefinitely behind lower-priority work.

This behavior is managed by the Darwin kernel via Mach scheduling policies and high-priority pthreads lanes - not something controlled explicitly by your code.

Task Priority

Swift provides a priority system for tasks, similar to Grand Central Dispatch (GCD), but more semantically integrated into the structured concurrency model. You can set a task’s priority via the Task initializer:

Task(priority: .userInitiated) { await loadUserData() }

The available priorities are defined by the TaskPriority enum:

| Priority | Description | |----|----| | .high / .userInitiated | For tasks initiated by user interaction that require immediate feedback. | | .medium | For tasks that the user is not actively waiting for. | | .low / .utility | For long-running tasks that don’t require immediate results, such as copying files or importing data. | | .background | For background tasks that the user is not directly aware of. Primarily used for work the user cannot see. |

Creating Tasks with Different Priorities

When you create a Task inside another task (default .medium priority), you can explicitly set a different priority for each nested task. Here, one child task is .low, and the other is .high. This demonstrates that priorities can be individually set regardless of the parent.

Task { // .medium by default Task(priority: .low) { print("\(1), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } Task(priority: .high) { print("\(2), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } } // 1, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x6000017040c0>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.low // 2, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x6000017040c0>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.high

If you don’t explicitly set a priority for a nested task, it inherits the priority of its immediate parent. In this example, the anonymous tasks inside .high and .low blocks inherit those respective priorities unless overridden.

Task Priorities Can Be Inherited

Task { Task(priority: .high) { Task { print("\(1), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } } Task(priority: .low) { print("\(2), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") Task { print("\(3), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } Task(priority: .medium) { print("\(4), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } } } // 2, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x600001708040>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.low // 1, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x600001708040>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.high // 3, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x600001708040>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.low // 4, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x600001708040>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.medium

If you don’t explicitly set a priority for a nested task, it inherits the priority of its immediate parent. In this example, the anonymous tasks inside .high and .low blocks inherit those respective priorities unless overridden.

Task Priority Escalation

Task(priority: .high) { Task { print("\(1), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } await Task(priority: .low) { print("\(2), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") await Task { print("\(3), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") }.value Task(priority: .medium) { print("\(4), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } }.value } // 1, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x6000017000c0>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.high // 2, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x6000017000c0>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.high // 3, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x6000017000c0>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.high // 4, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x6000017000c0>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.medium

This mechanism is called priority escalation — when a task is awaited by a higher-priority task, the system may temporarily raise its priority to avoid bottlenecks and ensure responsiveness.

As a result:

- Task 2, which is

.low, is escalated to.highwhile being awaited. - Task 3, which doesn’t have an explicit priority, inherits the escalated priority from its parent (Task 2) and is also executed with

.highpriority. - Task 4 explicitly sets its priority to

.medium, so it is not affected by escalation.

Task.detached Does Not Inherit Priority

Detached tasks (Task.detached) run independently and do not inherit the priority of their parent task. They behave like global tasks with their own scheduling. This is useful for isolating background work, but can also lead to unexpected priority mismatches if not set manually.

Task(priority: .high) { Task.detached { print("\(1), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } Task(priority: .low) { print("\(2), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") Task.detached { print("\(3), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } Task(priority: .medium) { print("\(4), "thread: \(Thread.current)", priority: \(Task.currentPriority)") } } } // 1, thread: <NSThread: 0x60000174dec0>{number = 4, name = (null)}, priority: TaskPriority.medium // 2, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x600001708180>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.low // 3, thread: <NSThread: 0x60000174dec0>{number = 4, name = (null)}, priority: TaskPriority.medium // 4, thread: <_NSMainThread: 0x600001708180>{number = 1, name = main}, priority: TaskPriority.medium

Suspension Points and How Swift Manages Async Execution

In Swift, any call to an async function using await is a potential suspension point - a place in the function where executing might pause and resume latter. It’s a transformation that involves saving the state of the function so it can be resumed latter, after awaited operation completes.

Here’s an example:

func fetchData() async -> String { let result = await networkClient.load() return result }

In this case, await networkClient.load() is a suspension point. When the function reaches this line, it may pause execution, yield control to the system, and later resume once load() finishes. Behind the scenes, the compiler transforms this function into a state machine that tracks its progress and internal variables.

Under the Hood: Continuations and State Machines

Every async function in Swift is compiled into a state machine. Each awaitmarks a transition point. Before reaching an await, Swift:

- Saves the current state of the function - including local variables and the current instruction pointer.

- Suspends execution and schedules a continuation.

- Once the async operation completes, it resumes the function from where it left off.

This is similar to the continuation-passing style (CPS) used in many functional programming systems. In Swift’s concurrency model, this is orchestrated by internal types like ParticialAsyncTask and the concurrency runtime scheduler.

Suspension != Blocking

When you await something in Swift, the current thread is not blocked, instead:

- The current task yields control back to the executor

- Other tasks can run while waiting

- When the awaited operation completes, the suspended task resumes on the appropriate executor.

This makes async/await fundamentally more efficient and scalable than thread-based blocking operations like DispatchQueue.sync.

Task.yield(): letting other tasks run

Task.yield() is a static method provided by Swift’s concurrency system that voluntarily suspends the current task, giving the system opportunity to run other enqueued tasks. It’s especially useful in long-running asynchronous operations or tight loops that don’t naturally contains suspension points.

func processLargeBatch() async { for i in 0..<1_000_000 { if i % 10_000 == 0 { await Task.yield() } } }

Without await, this loop would monopolize the executor. By inserting await Task.yield() periodically, you’re cooperating with Swift’s concurrency runtime, allowing to maintain responsivness and fairness.

Under the Hood

Calling await Task.yield() suspends the current task and re-enqueues it at the end of the queue for its current executor (e.g., main actor or a global concurrent executor). This allows other ready-to-run tasks to take their turn.

It’s part of Swift’s cooperative multitasking model: tasks run to the next suspension point and are expected to yield fairly. Unlike preemptive systems (e.g., threads), Swift tasks don’t get forcibly interrupted — they must voluntarily yield control.

Summary

Swift 6 marks a significant step forward in how concurrency is handled, offering developers more control, predictability, and safety. While the learning curve may be steep at first, understanding these concepts opens the door to building highly responsive and robust applications. As we continue exploring the deeper aspects of Swift’s new concurrency model, it’s clear that these changes lay the groundwork for the future of safe and scalable app development.

\n

\n

\

You May Also Like

Lyn Alden: The Fed is Printing Money, What Will Happen to BTC?

Goldman Sachs Warns $80 Billion in Forced Selling Could Still Hit U.S. Stocks